This paper synthesizes global evidence indicating that rice and rice based products are a major dietary source of inorganic arsenic, driven by flooded paddy cultivation that promotes arsenic mobilization and plant uptake. Across regions and product types, contamination levels vary substantially, yet risk assessments repeatedly indicate disproportionate non-carcinogenic and carcinogenic concern for infants and young children due to higher intake per kilogram body weight. The review emphasizes the toxicological centrality of speciation, noting that inorganic forms, particularly As(III), commonly dominate rice arsenic profiles and are less responsive to conventional household cooking than some other metals. Mitigation evidence supports upstream control, including alternate wetting and drying irrigation, cultivar selection, and targeted post-harvest processing approaches, as well as improved surveillance and consumer-facing risk communication. Regulatory fragmentation and inconsistent enforcement limit consumer protection and complicate trade. In this context, independent heavy metal certification can fill regulatory gaps by creating market incentives to meet best-in-class limits and by providing transparent testing data that can reassure caregivers while informing policy refinement. Future progress depends on harmonizing infant-food limits at ≤50 µg kg⁻¹, scaling agronomic interventions, and integrating climate-resilient water management to curb soil arsenic mobilization.

Inorganic arsenic, rice and rice-based products, infant and young child foods, arsenic speciation, HPLC-ICP-MS, health risk assessment, alternate wetting and drying (AWD), regulatory harmonization, third-party certification

Rice is a staple food for more than half the world’s population, yet it represents one of the primary dietary pathways for human exposure to inorganic arsenic (iAs), a well-established human carcinogen[1]. The accumulation of arsenic in rice is particularly problematic because rice plants are typically grown in flooded paddy fields, an anaerobic environment that promotes the mobilization and uptake of arsenic from soil and irrigation water[2]. This characteristic distinguishes rice from other cereal crops in terms of arsenic accumulation capacity.

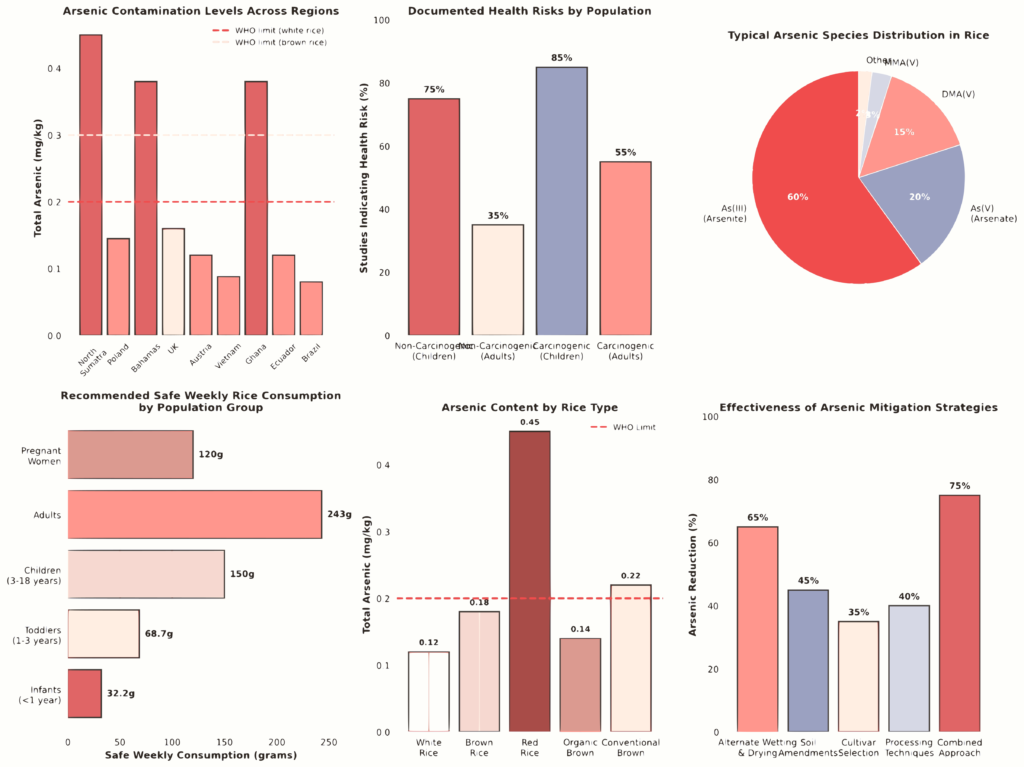

A comprehensive survey across multiple regions reveals substantial geographic variation in rice arsenic contamination. Surbakti and colleagues documented significant regional differences in North Sumatra, Indonesia, where white rice samples generally contained arsenic levels below the World Health Organization (WHO) limit of 0.3 mg/kg, with concentrations ranging from 0.0011 to 0.0084 mg/kg[3]. In contrast, red rice exhibited the highest contamination, with 11 out of 13 samples exceeding the WHO safety threshold, with some surpassing 0.9 mg/kg. Brown rice showed intermediate concentrations ranging from 0.0002 to 0.2388 mg/kg, with samples from certain regions approaching or exceeding WHO limits.

Rice is a staple food for more than half the world’s population, yet it represents one of the primary dietary pathways for human exposure to inorganic arsenic (iAs), a well-established human carcinogen [1]. The accumulation of arsenic in rice is particularly problematic because rice plants are typically grown in flooded paddy fields, an anaerobic environment that promotes the mobilization and uptake of arsenic from soil and irrigation water [2]. This characteristic distinguishes rice from other cereal crops in terms of arsenic accumulation capacity.

A comprehensive survey across multiple regions reveals substantial geographic variation in rice arsenic contamination. Surbakti and colleagues documented significant regional differences in North Sumatra, Indonesia, where white rice samples generally contained arsenic levels below the World Health Organization (WHO) limit of 0.3 mg/kg, with concentrations ranging from 0.0011 to 0.0084 mg/kg [3]. In contrast, red rice exhibited the highest contamination, with 11 out of 13 samples exceeding the WHO safety threshold, with some surpassing 0.9 mg/kg. Brown rice showed intermediate concentrations ranging from 0.0002 to 0.2388 mg/kg, with samples from certain regions approaching or exceeding WHO limits.

The geographic distribution of arsenic contamination in rice is influenced by both natural geological factors and anthropogenic sources [4]. In endemic arsenic regions such as Bangladesh, Vietnam, and parts of South Asia, dietary arsenic exposure through rice consumption ranges from 250 to 650 g per person daily in Southeast Asian countries, making rice consumption one of the leading causes of human arsenic exposure in these populations. The European Commission has established maximum inorganic arsenic levels of 0.20 mg/kg for white rice and 0.25 mg/kg for brown rice, with stricter limits of 0.1 mg/kg for rice intended for infants and young children [5]. Studies examining rice from different markets consistently reveal that a significant proportion of commercially available rice products exceed these regulatory thresholds.

| Region | Total Arsenic (mg/kg) | Inorganic Arsenic (mg/kg) | Sample Size | Regulatory Status |

| North Sumatra, Indonesia (White) | 0.006-0.008 | Below WHO limit | 13 | Within limits |

| North Sumatra, Indonesia (Red) | 0.2-0.9 | 0.1-0.6 | 13 | Exceeds limits |

| Poland | 0.145 | 0.098-0.130 | 33 | Within limits |

| The Bahamas | 0.38 | 0.200-0.240 | 21 | Exceeds WHO |

| United Kingdom | 0.16 | 0.095-0.130 | 55 | Mostly within |

| Austria | 0.12 | 0.077-0.237 | 51 | Within limits |

| Vietnam (HCM City) | 0.088 | 0.075 | 60 | Within limits |

| Ghana | 0.38 | 0.256-0.505 | 11 | Exceeds CODEX |

| Ecuador | 0.12 | 0.096 | 31 | Within limits |

Data sources: Rajkowska-Myliwiec et al. (2024), Surbakti et al. (2025), Watson & Gustave (2022), Menon et al. (2020), Dressler et al. (2023), Phan et al. (2020), Bartels et al. (2023), Gavilanes-Tern et al. (2019)

Understanding arsenic speciation is critical for assessing actual human health risks, as the toxicity of arsenic compounds varies dramatically depending on their chemical form and oxidation state [6]. Inorganic arsenic species, particularly arsenite (As(III)) and arsenate (As(V)), are significantly more toxic and carcinogenic than organic arsenic species such as dimethylarsinic acid (DMA(V)) and monomethylarsonic acid (MMA(V)). The Joint Food and Agriculture Organisation/World Health Organisation Expert Committee on Food Additives has determined that inorganic arsenic poses approximately 100-fold greater toxicity than the organic form [1].

Speciation studies conducted across different rice-producing regions provide consistent findings regarding arsenic species distribution in rice products. Research utilizing high-performance liquid chromatography coupled with inductively coupled plasma mass spectrometry (HPLC-ICP-MS) has consistently identified arsenite (As(III)) as the predominant arsenic species in rice, accounting for 60-80% of total arsenic content [7]. This finding is particularly significant because As(III) is more mobile in the environment and more readily absorbed by rice plants than As(V). Guillod-Magnin and colleagues, analyzing rice products specifically intended for toddlers in Switzerland, found that As(III) predominated with 60-80% of total arsenic, followed by DMA(V) and As(V), with MMA(V) measured only at low levels (<3%) [7].

The persistence of inorganic arsenic through food processing adds further concern [8]. Analysis of cooked rice from 30 Indonesian provinces revealed that while cooking reduced cadmium content by 76%, arsenic levels remained essentially unchanged after cooking, suggesting that thermal processing does not effectively reduce inorganic arsenic exposure. This characteristic distinguishes arsenic from other heavy metals and indicates that mitigation strategies must occur at the agricultural or post-harvest processing level rather than during meal preparation.

Comprehensive health risk assessment of arsenic in rice requires application of standardized toxicological frameworks that evaluate both carcinogenic and non-carcinogenic endpoints [9]. The most widely employed metrics include the Hazard Quotient (HQ), Target Hazard Quotient (THQ), Hazard Index (HI), Excess Cancer Risk (ECR), Margin of Exposure (MOE), and Incremental Lifetime Cancer Risk (ILCR). These metrics are compared against reference values established by international regulatory bodies including the European Food Safety Authority (EFSA), the World Health Organization (WHO), and the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA).

The EFSA recently established a benchmark dose lower confidence limit for a 0.5% increased incidence of lung cancer (BMDL₀.₅) of 0.06 μg iAs/kg body weight per day based on epidemiological evidence from skin cancer studies [6]. This represents a significantly more stringent limit than the previous WHO guidance and reflects growing evidence of arsenic’s carcinogenic potential at lower exposure levels. In contrast, chronic daily intakes observed in high-consuming populations frequently exceed these safety thresholds, indicating widespread health concern.

The application of probabilistic risk assessment methods using Monte Carlo simulation has enhanced the precision of health risk evaluation by accounting for inter-individual variability in body weight, consumption patterns, and absorption rates [10]. Health risk assessment studies consistently demonstrate that children face substantially higher non-carcinogenic and carcinogenic risks from arsenic in rice compared to adults. Navaretnam and colleagues, utilizing HPLC-ICP-MS speciation analysis and health risk assessment of white and brown rice in Malaysia, found that all rice samples evaluated showed a target hazard quotient above 1, indicating potential non-carcinogenic health risks [11]. Furthermore, estimated cancer risks exceeded the 10⁻³ threshold under revised cancer slope factor values.

Infants and young children represent particularly vulnerable populations for arsenic exposure through rice consumption, both due to their increased dietary intake relative to body weight and the potential for developmental toxicity [12]. Rice products, including infant cereals, rice-based formula thickeners, and infant foods, are ubiquitous in pediatric diets, particularly for infants diagnosed with gastroesophageal reflux disease. The 2015 Food and Drug Administration investigation demonstrated that rice products used to thicken infant feeds contained unsafe levels of inorganic arsenic, with particular concern regarding the use of rice cereal as an anti-reflux thickener.

Signes-Pastor and colleagues conducted longitudinal analysis of urinary arsenic metabolites in infants transitioning from formula to solid foods, documenting substantial increases in urinary monomethylarsonic acid (MMA) and dimethylarsinic acid (DMA) following weaning with rice-based products [13]. Comparing rice-based infant foods marketed before and after European Union inorganic arsenic regulations implemented January 1, 2016, the researchers found that nearly one-half of rice-based products specifically marketed for infants and young children contained inorganic arsenic exceeding the 0.1 mg/kg EU limit. This suggests that regulatory limits alone, without enforcement mechanisms and market compliance monitoring, may provide insufficient protection for vulnerable infant populations.

Risk assessment calculations for Polish consumers established evidence-based consumption thresholds to minimize carcinogenic risk: infants up to one year of age should consume no more than 32.2 g of rice-based products per week, children under three years of age up to 68.7 g, and adults 243 g [1]. These recommendations represent substantial reductions from current consumption patterns in high-rice-consuming populations and highlight the degree of health concern regarding arsenic in rice for young children.

Pregnant women represent another vulnerable population due to potential placental transfer of arsenic and fetal developmental toxicity [14]. A prospective study of Hispanic/Latino pregnant women in the Hispanic Community Health Study/Study of Latinos found that among participants with high rice consumption (>5.0 servings/day), each standard deviation increase in arsenic-related DNA methylation score was associated with a 61% increased risk of incident type 2 diabetes, whereas this association was absent among those with low/intermediate rice consumption. This finding suggests that arsenic exposure through rice consumption may have metabolic consequences that extend beyond cancer risk, particularly for genetically susceptible populations.

| Population Group | Location | Study | Key Finding | ILCR/HQ | Reference |

| Infants (high consumption) | Poland | Rajkowska-Myliwiec et al. | 3× consumption increases risk substantially | >1.0 | [1] |

| Toddlers (1-3 years) | Switzerland | Guillod-Magnin et al. | High iAs from rice cereals | >1.0 | [7] |

| Children | Kunming, China | Liao et al. | ILCR 5× above US limit | 5×10⁻⁴ | [15] |

| Children | East Java, Indonesia | Laela et al. | HQ >1, ECR >10⁻⁴ | >1.0 | [16] |

| Pregnant women | US/Hispanic/Latino | Li et al. | 61% increased T2D risk with high rice | Significant | [14] |

| Adolescents | Kunming, China | Liao et al. | ILCR 5× above acceptable limit | 5.28×10⁻⁴ | [15] |

Chronic exposure to inorganic arsenic has been definitively established as causative of multiple malignancies including lung, skin, and bladder cancers, as well as non-malignant health effects affecting the cardiovascular, neurological, endocrine, immune, and reproductive systems [9]. The International Agency for Research on Cancer classified inorganic arsenic as a Group 1 human carcinogen, indicating sufficient evidence for carcinogenicity in humans.

Beyond cancer endpoints, emerging evidence demonstrates arsenic-related metabolic dysfunction, immune suppression, and developmental effects. Research examining arsenic exposure and diabetes risk has identified significant associations between urinary arsenic levels and type 2 diabetes incidence across multiple populations [14]. The mechanisms underlying arsenic-induced diabetes appear to involve both direct pancreatic β-cell toxicity and systemic metabolic effects, with evidence suggesting that gut microbiota composition may modulate individual susceptibility to arsenic-related carcinogenic effects [17].

Studies of arsenic bioavailability in rice bran products, which accumulate higher arsenic concentrations than the endosperm, revealed that human gut microbiota could significantly transform arsenic species through methylation pathways [18]. In vitro colon fermentation studies demonstrated that arsenic bioaccessibility declined from 66.0-95.8% in the small intestinal phase to 11.3-63.6% in the colon phase, with methylation percentages of 18.5-79.8%. These findings suggest that food-bound arsenic undergoes substantial biotransformation in the human digestive system, potentially influencing individual differences in toxicity.

Neurological and developmental effects have been documented in populations with elevated arsenic exposure during critical developmental windows [4]. The Middle East review on dietary arsenic exposure identified that arsenic exposure might be a causative factor in the alarming rise of neurological deficit disorder and autism spectrum disorder cases in some regions, warranting population screening and reassessment of arsenic limits across all age groups.

Evidence-based mitigation strategies for reducing arsenic in rice include irrigation management practices, soil and foliar amendments, cultivar selection, and post-harvest processing [2]. Alternate wetting and drying (AWD) irrigation has emerged as a high-effectiveness mitigation approach that decreases grain arsenic concentrations while also providing climate-smart benefits and remaining cost-neutral for farmers. The mechanism underlying AWD effectiveness involves the elevation of soil redox potential (Eh), which suppresses arsenic mobilization from soil and reduces plant uptake.

Field studies comparing three irrigation regimes—alternating wetting and drying (AWD), continuous flooding (CF), and rice-crayfish farming systems (RCFS)—demonstrated that soil arsenic safety thresholds varied substantially by management approach [19]. For AWD systems, the estimated soil arsenic safety threshold was 26.48 mg/kg, substantially higher than for CF (9.24 mg/kg) and RCFS (11.98 mg/kg). The superior performance of AWD reflected its ability to elevate soil Eh and maintain favorable pH conditions, thereby suppressing arsenic mobilization. Combining irrigation management with carefully selected soil amendments maximized the decrease in grain arsenic concentrations.

Foliar applications of brassinolide and selenium have demonstrated effectiveness in reducing arsenic and cadmium accumulation in rice grains [20]. Application of 20 mM brassinolide combined with 1 mM selenium at the grain-filling stage resulted in the lowest arsenic (0.149 mg/kg) and cadmium (0.105 mg/kg) accumulation, with health risk indices below acceptable limits. These applications improved photosynthesis, reduced oxidative stress markers, and enhanced grain nutrient uptake while simultaneously reducing toxic metal concentrations.

Natural variation in arsenic accumulation among rice cultivars provides opportunities for breeding and selection of low-arsenic varieties [21]. Evaluation of 120 rice accessions, comprising landraces and farmer varieties grown under naturally arsenic-contaminated conditions in Chhattisgarh, India, identified substantial variation in grain arsenic accumulation. Cultivated varieties (Badsabhog Sel 1 and Bahadur Sel 1) and landraces (Bastul and Kanaklata) exhibited the lowest grain-arsenic accumulation and could serve as valuable donors in breeding programs. However, correlation analysis revealed no significant relationship between grain-arsenic accumulation and agronomic traits, indicating that low-arsenic phenotypes represent complex, multigenic traits requiring specific screening approaches.

Several post-harvest processing techniques have shown potential for reducing arsenic concentrations in rice products. Parboiling before absorption cooking (PBA) demonstrated substantial effectiveness in reducing toxic metal contamination in Malaysian rice, eliminating 77.9% of toxic metals and 68.4% of essential metals [10]. Importantly, PBA reduced the lifetime carcinogenic risk (LCR) from arsenic exposure by 88.9% when compared to standard cooking methods. Alternative approaches combining yeast-based biological treatment with ultrasonic waves showed promise for arsenic reduction, with combined treatment achieving approximately 83% arsenic reduction in cooked rice samples [22].

Cost-effective extraction methods for inorganic arsenic assessment in resource-limited settings have been developed and validated [23]. Coke extraction demonstrated high recovery of inorganic arsenic (127.4%) with strong correlation to the standard nitric acid method (Pearson correlation coefficient 0.990), suggesting potential for field-deployable arsenic testing in developing countries where laboratory infrastructure is limited.

The Codex Alimentarius Commission has established maximum inorganic arsenic levels of 0.2 mg/kg for white rice and 0.3 mg/kg for brown rice [8]. However, the European Union implemented more stringent limits of 0.2 mg/kg for white rice and 0.25 mg/kg for brown rice, while establishing an especially protective limit of 0.1 mg/kg for rice-based products intended for infants and young children. These divergent regulatory approaches reflect ongoing scientific debate regarding appropriate risk management thresholds.

The WHO recently revised reference dose guidance for inorganic arsenic, establishing a BMDL₀.₅ of 0.06 μg/kg body weight per day based on epidemiological evidence from skin cancer studies [24]. This updated guideline is substantially more stringent than previous guidance and reflects cumulative evidence of arsenic toxicity at lower exposure levels. Studies comparing actual dietary exposure to these revised limits reveal that substantial portions of rice-consuming populations exceed safety thresholds.

Enforcement of regulatory standards varies substantially across regions. Analysis of rice and rice products available in the Austrian market revealed that while mean inorganic arsenic concentrations in rice varieties (120 μg/kg), rice products (191 μg/kg), and baby foods (77 μg/kg) were below EU maximum levels, the highest concentration in rice flakes (237 μg/kg) approached the limit established for husked rice [25]. Notably, upland-grown rice from Austria showed both low inorganic arsenic (<19 μg/kg) and cadmium (<38 μg/kg) concentrations, suggesting that cultivation location and practices substantially influence final product contamination.

Consumer knowledge regarding arsenic contamination in rice remains limited in many regions. A cross-sectional study of Kurdish consumers revealed that 51% of 282 participants did not know that rice contains arsenic or causes health issues [26]. However, when informed about arsenic contamination, 72% of participants decided they would reduce their rice consumption, and 88% indicated that information about arsenic would help them reconsider their consumption patterns. These findings suggest that consumer awareness campaigns and transparent labeling could substantially modify consumption behaviors and reduce population-level exposure.

| Regulatory Body | White Rice (mg/kg) | Brown Rice (mg/kg) | Infant Products (mg/kg) | Scientific Basis |

| Codex Alimentarius | 0.2 | 0.3 | — | Risk assessment (JECFA) |

| European Union | 0.2 | 0.25 | 0.1 | Cancer risk (EFSA) |

| WHO (Previous) | 0.3 | 0.3 | — | Risk assessment (JECFA) |

| WHO (Current BMDL₀.₅) | — | — | — | Skin cancer (0.06 μg/kg bw/day) |

| USA (FDA Guidance) | 0.1 | — | 0.1 | Risk assessment |

| China | 0.2 | — | — | Risk assessment |

The question of whether brown rice consumption, often promoted as nutritionally superior to white rice due to its bran content, outweighs the increased arsenic exposure presents a complex risk-benefit analysis [27]. Brown rice contains significantly higher concentrations of essential trace elements including selenium, zinc, copper, iron, and manganese compared to white rice, with organic brown rice containing more essential elements than conventionally grown brown rice [28]. However, brown rice also accumulates substantially higher arsenic concentrations than white rice due to arsenic enrichment in the bran layer.

Comparative analysis of arsenic exposure between brown and white rice consumers reveals higher estimated arsenic exposures in regular brown rice consumers [29]. Americans consuming brown rice regularly were found to have substantially higher estimated arsenic exposures than white rice consumers. However, the same analysis found no acute public health risks indicated for the general American population from rice-related arsenic exposures overall, suggesting that while risk exists, absolute risk at current consumption levels remains manageable for most populations.

Nevertheless, rice-based dietary guidance should consider both carcinogenic and non-carcinogenic endpoints and incorporate age-specific recommendations. Children represent a particularly vulnerable population due to their higher consumption relative to body weight, and dietary diversification with multiple cereal sources rather than rice-dominant diets represents an evidence-based approach to reducing arsenic exposure [1]. Consumers should be advised to include a variety of cereals in their daily diet and choose products shown to have low arsenic contamination levels based on testing and inspection rankings.

| Health Outcome | Population | Evidence Level | References |

| Lung Cancer (Carcinogenic) | Adults/Children | Strong (Epidemiologic) | [9], [15] |

| Skin Cancer (Carcinogenic) | Adults | Strong (Epidemiologic) | [6], [24] |

| Bladder Cancer (Carcinogenic) | Adults | Strong (Epidemiologic) | [9], [17] |

| Type 2 Diabetes | High rice consumers | Moderate (Cohort) | [14] |

| Cardiovascular Disease | Adults | Moderate (Epidemiologic) | [9] |

| Neurodevelopmental Effects | Children/Prenatal | Moderate (Mixed) | [4] |

| Immune Dysfunction | Children | Limited (Animal) | [9] |

| Skin Lesions (Non-malignant) | Chronic exposures | Strong (Epidemiologic) | [9] |

Arsenic contamination in rice-based products represents a significant global public health concern, affecting billions of individuals who rely on rice as a dietary staple. The evidence synthesized in this literature review demonstrates that arsenic contamination is widespread across major rice-producing regions, with substantial variability driven by geographic factors, cultivation practices, and rice type. This heterogeneity complicates risk management and underscores the need for context-specific mitigation strategies rather than a single universal solution.

The health implications are not evenly distributed across populations. Infants, young children, and pregnant women experience disproportionately higher carcinogenic and non-carcinogenic risks from rice-based arsenic exposure due to higher intake relative to body weight and increased physiological vulnerability during critical developmental periods. These findings reinforce the importance of exposure reduction strategies that specifically prioritize protection of vulnerable groups rather than relying solely on population-wide averages.

The review also highlights that multiple mitigation strategies are both available and effective. Agronomic interventions, including alternate wetting and drying irrigation, careful cultivar selection, and targeted post-harvest processing methods, have demonstrated meaningful reductions in arsenic accumulation in rice grains. When implemented together, these approaches offer practical pathways for lowering exposure at the source, although their adoption remains uneven across regions and production systems.

A major barrier to effective consumer protection is regulatory fragmentation. Divergent arsenic limits, inconsistent enforcement, and varying analytical requirements across jurisdictions weaken public health safeguards and introduce inequities in international trade. These inconsistencies make it difficult for consumers to interpret risk and for producers to align with best practices, further highlighting the need for harmonized, science-based standards.

Despite substantial progress, important knowledge gaps remain. Uncertainties related to arsenic bioavailability, species-specific toxicity, and gene–environment interactions limit the precision of current risk assessments and warrant continued investigation. Future research should prioritize large-scale, commercial implementation trials of agronomic mitigation strategies, alongside the development of culturally appropriate dietary guidance that balances arsenic risk with nutritional adequacy. Additional priorities include global standardization of regulatory limits grounded in consistent scientific evidence, strengthened surveillance systems to monitor contamination trends and population exposures, and mechanistic studies examining links between arsenic exposure and metabolic diseases such as type 2 diabetes. Finally, emerging evidence suggests that diet–gut microbiota interactions may offer novel avenues to attenuate arsenic toxicity in high-risk populations, representing a promising direction for future intervention research.

[1] R.-M. M, C. A, and K. G, “Arsenic in Rice and Rice-Based Products with Regard to Consumer Health.,” Oct. 2024, doi: 10.3390/foods13193153.

[2] L. Me, R. Ml, S. Al, and R. Brk, “Agronomic solutions to decrease arsenic concentrations in rice.,” May 2025, doi: 10.1007/s10653-025-02508-7.

[3] C. Surbakti, J. Silalahi, A. Arianto, and U. Harahap, “Determination of Arsenic Contamination in Rice Grains from Multiple Sites in North Sumatra, Indonesia,” African Journal of Food, Agriculture, Nutrition and Development, Dec. 2025, doi: 10.18697/ajfand.147.26120.

[4] M. Khan et al., “Arsenic Exposure through Dietary Intake and Associated Health Hazards in the Middle East,” Nutrients, May 2022, doi: 10.3390/nu14102136.

[5] M. Menon, B. Sarkar, J. Hufton, C. Reynolds, S. V. Reina, and S. D. Young, “Do arsenic levels in rice pose a health risk to the UK population?,” Elsevier BV, Apr. 2020, doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecoenv.2020.110601.

[6] S. W. C. Chung, “Feasible approaches for arsenic speciation analysis in foods for dietary exposure assessment: a review,” Food Additives and Contaminants Part A-chemistry Analysis Control Exposure & Risk Assessment, Jan. 2025, doi: 10.1080/19440049.2025.2449663.

[7] R. Guillod-Magnin, B. Brschweiler, R. Aubert, and M. Haldimann, “Arsenic species in rice and rice-based products consumed by toddlers in Switzerland,” Food Additives and Contaminants Part A-chemistry Analysis Control Exposure & Risk Assessment, Feb. 2018, doi: 10.1080/19440049.2018.1440641.

[8] Y. F, F. Dn, A. N, and rednicka-T. D, “The Concentration of Potentially Toxic Elements (PTEs) in Indonesian Rice and Their Health Risk Assessment.,” Oct. 2025, doi: 10.3390/foods14213652.

[9] V. P, “Arsenic in Water and Food: Toxicity and Human Exposure.,” Jun. 2025, doi: 10.3390/foods14132229.

[10] N. C. Goh, N. S. Noor, R. Mohamed, A. Tualeka, M. A. Zabidi, and M. Y. Aziz, “Health risk assessment of metal contamination in Malaysian rice (Oryza sativa): The impact of parboiling on toxic metal reduction prior to cooking,” International Journal of Food Science & Technology, Sep. 2024, doi: 10.1111/ijfs.17566.

[11] N. R et al., “Arsenic speciation using HPLC-ICP-MS in white and brown rice and health risk assessment.,” Aug. 2025, doi: 10.1007/s10653-025-02723-2.

[12] R. W. D. Jong, K. G. Andren, P. T. Reeves, and S. Bowe, “Arsenic in Rice: A Call to Change Feeding Substitution Practices for Pediatric Otolaryngology Patients.,” Otolaryngology Head & Neck Surgery, Oct. 2024, doi: 10.1002/ohn.1029.

[13] A. Signes-Pastor et al., “Levels of infants urinary arsenic metabolites related to formula feeding and weaning with rice products exceeding the EU inorganic arsenic standard,” PLoS ONE, May 2017, doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0176923.

[14] X. Li et al., “1482-P: Arsenic-Related DNA Methylation and Incident Type 2 Diabetes in the Hispanic Community Health Study/Study of Latinos (HCHS/SOL),” Diabetes, Jun. 2025, doi: 10.2337/db25-1482-p.

[15] N. Liao, E. Seto, B. Eskenazi, M.-C. Wang, Y. Li, and J. Hua, “A Comprehensive Review of Arsenic Exposure and Risk from Rice and a Risk Assessment among a Cohort of Adolescents in Kunming, China,” International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, Oct. 2018, doi: 10.3390/ijerph15102191.

[16] N. Laela, S. A. Pasma, and M. Santoso, “Arsenic Levels in Soil and Rice and Health Risk Assessment via Rice Consumption in Industrial Areas of East Java, Indonesia,” Environment and Natural Resources Journal, Aug. 2023, doi: 10.32526/ennrj/21/20230049.

[17] S. L and L. C, “The modifying effect of dietary index for gut microbiota on the association between urinary arsenic exposure and bladder cancer risk: a nationwide cohort study.,” Dec. 2025, doi: 10.3389/fnut.2025.1723496.

[18] N. Yin et al., “Arsenic in Rice Bran Products: In Vitro Oral Bioaccessibility, Arsenic Transformation by Human Gut Microbiota, and Human Health Risk Assessment.,” Journal of Agricultural and Food Chemistry, Apr. 2019, doi: 10.1021/acs.jafc.9b02008.

[19] K. Zhang et al., “Study on the Bioavailability of Arsenic in the RiceCrayfish Farming System,” Fishes, Dec. 2025, doi: 10.3390/fishes10120645.

[20] X. Lan et al., “Effects of foliar applications of Brassinolide and Selenium on the accumulation of Arsenic and Cadmium in rice grains and an assessment of their health risk,” International journal of phytoremediation, May 2022, doi: 10.1080/15226514.2022.2066064.

[21] S. Ps et al., “Grain arsenic accumulation is independent of agronomic traits in rice under field conditions.,” Jun. 2025, doi: 10.1007/s12298-025-01597-z.

[22] S. B, Y. R, H. H, S. E, and F. E, “Action plan strategies for a new approach to the combination of yeast and ultrasonic waves for the reduction of heavy metal residues in rice.,” Nov. 2024, doi: 10.1038/s41598-024-79560-3.

[23] M. At et al., “Development of cost-effective inorganic arsenic extraction method for resource-limited regions: Analysis of efficiency and regulatory implications.,” Sep. 2024, doi: 10.1016/j.heliyon.2024.e37784.

[24] A. Mm, R.-S. A, S. I, and P. Da, “Chemical analysis of toxic elements: total cadmium, lead, mercury, arsenic and inorganic arsenic in local and imported rice consumed in the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia.,” Nov. 2024, doi: 10.1007/s10653-024-02280-0.

[25] J. M. Dressler, A. Raab, S. Wehmeier, and J. Feldmann, “Arsenic, cadmium, and lead in rice and rice products on the Austrian market,” Food Additives & Contaminants, Part B, Apr. 2023, doi: 10.1080/19393210.2023.2194061.

[26] B. Sadee, Y. Galali, S. M. S. Zebari, S. Nawzad, S. Khalid, and B. Sardar, “Assessing the Knowledge of Kurdish Consumers about the Presence and Health Impacts of Arsenic in Rice,” 5th International Conference on Biomedical and Health Sciences, 2024, doi: 10.24086/biohs2024/paper.1266.

[27] L. Su, T. Chiang, and S. O’Connor, “Arsenic in brown rice: do the benefits outweigh the risks?,” Frontiers in Nutrition, Jul. 2023, doi: 10.3389/fnut.2023.1209574.

[28] R. S. I et al., “Dietary Trace Elements and Arsenic Species in Rice: A Study of Samples from Croatian Supermarkets.,” Jun. 2025, doi: 10.3390/foods14132261.

[29] S. Ck and W. F, “Arsenic content and exposure in brown rice compared to white rice in the United States.,” Feb. 2025, doi: 10.1111/risa.70008.

[30] K. E. Nachman, G. L. Ginsberg, M. Miller, C. J. Murray, A. E. Nigra, and C. Pendergrast, “Mitigating dietary arsenic exposure: Current status in the United States and recommendations for an improved path forward,” Elsevier BV, Jan. 2017, doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scitotenv.2016.12.112.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

Likelihood of Pear, Kale, and Spinach Purée Passing HMTc Standards: An Analysis

Likelihood of Pear, Kale, and Spinach Purée Passing HMTc Standards: An Analysis

Cadmium Exposure in Protein Powders: Risk Assessment and Remediation

Cadmium Exposure in Protein Powders: Risk Assessment and Remediation