This review (2019–2024) synthesizes evidence on lead contamination in children’s vitamins and highlights a core consumer-protection paradox: products marketed to support pediatric health have, in some cases, contained a neurotoxic contaminant that undermines that goal. Although reported incidents are not ubiquitous, they have been sufficiently consequential to trigger recalls, legal actions, and heightened regulatory scrutiny, with consumer advocacy and independent testing (including third-party investigators) repeatedly serving as the primary detection and accountability mechanisms. The findings support a shift from reactive response to prevention through systematic, third-party heavy metal testing and certification, which can both intercept contaminated products and substantiate responsible brands’ quality claims as analytical costs fall and validated methods (for example, ICP-MS panels) become increasingly accessible. Regulatory momentum toward transparency, including California’s AB-899 and broader U.S. attention to lowering allowable lead in children’s consumables, suggests that posting results and meeting stricter internal specifications will become an operational expectation rather than a differentiator. Because globalized ingredient sourcing can introduce region-dependent variability in lead burden, robust supplier vetting and harmonization of limits are emphasized. Overall, the review concludes that while acute poisonings linked to vitamins appear rare, the priority is eliminating subclinical, cumulative lead exposure through cleaner inputs, verified manufacturing controls, independent certification, and consumer-facing transparency so that “essentially zero” lead becomes the industry baseline rather than a competitive advantage.

Lead contamination, children’s vitamins, heavy metals, dietary supplements, consumer safety;, heavy metal testing, regulation, neurotoxicity

Lead contamination in dietary supplements, particularly children’s vitamins, has emerged as a significant public health concern in recent years. Lead (Pb) is a naturally occurring heavy metal that poses serious health risks, especially to vulnerable populations including pregnant women, developing fetuses, and young children [1]. The widespread use of dietary supplements has increased substantially across all age groups, with approximately one-third of children in the United States consuming at least one dietary supplement [2]. However, the regulatory landscape governing dietary supplements differs markedly from pharmaceutical products, creating potential gaps in safety oversight and quality control [3].

The problem is particularly acute because children’s vitamins and dietary supplements may contain lead from multiple sources, including contaminated raw materials, manufacturing processes, and inadequate quality control measures. Studies conducted between 2019 and 2024 have documented lead contamination in various supplement formulations available globally, with concentrations sometimes exceeding international safety standards [4]. This comprehensive review synthesizes current evidence on lead contamination in children’s vitamins, examining its sources, health implications, detection methods, and regulatory frameworks.

2.1 Search Strategy

A systematic literature review was conducted to identify relevant studies published between 2019 and 2024. Comprehensive searches were performed across multiple academic databases including PubMed, Web of Science, Scopus, and EMBASE using the following keywords: “lead contamination,” “children’s vitamins,” “dietary supplements,” “heavy metals,” “consumer safety,” “heavy metal testing,” “regulation,” “neurotoxicity,” “mismetallation,” and “microbial metallomics.” The search strategy combined these terms using Boolean operators (AND, OR) to maximize retrieval of relevant publications.

2.2 Inclusion Criteria

Studies were included if they: (1) focused on lead or heavy metal contamination in dietary supplements, vitamins, or related food products marketed for or consumed by children; (2) reported analytical data on lead concentrations or contamination rates; (3) provided health risk assessments related to lead exposure; (4) discussed regulatory frameworks or detection methodologies; (5) examined neurotoxicological effects of lead in children; or (6) were published in English between 2019 and 2024. Studies examining historical lead exposure sources (paints, gasoline) were included when relevant to contextualizing current risk factors.

2.3 Data Extraction and Synthesis

Data were extracted systematically from each included study, documenting: study design and sample characteristics, lead contamination levels (concentrations and prevalence rates), product categories analyzed, analytical methodologies employed, health risk assessments, regulatory standards applied, and neurological outcomes measured. Information was organized thematically into major sections covering contamination sources and occurrence, health effects and neurotoxicity mechanisms, analytical detection methods, and regulatory frameworks. A narrative synthesis approach was employed given the heterogeneity in study designs, geographic origins, and outcome measures.

2.4 Limitations

This review is subject to several limitations. First, publication bias may exist favoring studies with positive findings of contamination. Second, while extensive searches were performed, the rapidly evolving literature and variations in nomenclature for dietary supplements may have resulted in missed relevant publications. Third, differences in analytical methodologies, sampling protocols, and regulatory standards across countries make direct comparisons challenging. Fourth, limited longitudinal studies specifically examining long-term health effects of supplement-derived lead exposure in children preclude definitive causal inferences. Finally, access to unpublished regulatory data from manufacturers was restricted, potentially underestimating actual contamination rates in some product categories.

3.1 Prevalence of Lead Contamination in Children’s Vitamins

Recent investigations have documented substantial variation in lead contamination across different vitamin and supplement formulations. A comprehensive analysis of dietary supplements available in various international markets revealed that adaptogenic supplements demonstrated the highest contamination rates, with lead concentrations exceeding permissible limits by up to 235% [4]. Similarly, assessment of Mexican dietary supplements found mean lead concentrations of 1.99 ± 0.13 mg/kg, with 80% of products showing estimated daily intakes within acceptable limits, though certain products still exceeded reference values [5].

Evaluation of multivitamin products specifically identified concerning lead levels in commercially available formulations [6]. An examination of herbal supplements in the United States found that while lead detection rates were lower than expected, the high variability in contaminant levels both within and between bottles of identical products raised serious concerns about quality control during manufacturing [7]. These findings suggest that contamination is not uniformly distributed across supplement types, with processed forms (tablets) showing greater contamination than dried materials or powders [4].

3.2 Sources and Pathways of Lead Contamination

Lead contamination in dietary supplements originates from multiple sources that can be broadly categorized as raw material contamination, manufacturing process contamination, and environmental exposure during storage and distribution. Raw plant materials used in herbal supplements often accumulate lead from contaminated soils, agricultural practices, and atmospheric deposition [8]. The bioavailability of lead in soil and its uptake by plants varies depending on soil pH, organic matter content, and mineral composition, with more acidic soils facilitating greater plant uptake [9].

Manufacturing processes contribute significantly to lead contamination through several mechanisms. Equipment used in processing may contain lead-based components, and inadequate cleaning between production batches can lead to cross-contamination [10]. Additionally, packaging materials—particularly ceramic containers with lead-based glazes or older storage vessels—may contribute to lead leaching into supplement contents. Geographic origin of raw materials is particularly important, with products sourced from regions with higher environmental lead pollution showing elevated contamination rates [4].

The source of raw materials significantly influences lead content. Raw materials from India contained significantly higher nickel and lead concentrations compared to those from China in adaptogenic supplements, suggesting geographically variable environmental pollution [4]. Similarly, supplements derived from countries with inadequate environmental regulations or higher industrial lead emissions showed systematically elevated contamination levels [5].

3.3 Product Categories and Risk Stratification

Analysis of different supplement categories reveals distinct contamination patterns. Heavy metal contamination assessment in infant formula and complementary foods found that aluminum, cobalt, chromium, copper, iron, and zinc frequently exceeded FAO/WHO standards, with all hazard indices exceeding the safety threshold [11]. Protein powder supplements demonstrated particularly concerning contamination levels, with 52% of samples showing lead concentrations exceeding safety standards [12].

Weight loss and dietary supplements showed variable contamination, with certain herbal-based formulations exceeding regulatory limits for both lead and cadmium [13]. Specialized dietary supplements designed for vulnerable populations, including infant formulas and fortified foods, warrant particular attention due to the susceptibility of these populations to lead toxicity. These products represent a critical control point where regulatory oversight and quality assurance become paramount [14].

4.1 Mechanisms of Lead Neurotoxicity

Lead exerts its neurotoxic effects through multiple interconnected biological mechanisms that collectively result in impaired cognitive and behavioral development. The fundamental toxicological mechanism involves lead’s ability to disrupt crucial cellular processes including neurotransmission, calcium signaling, and synaptic plasticity [15]. Lead readily crosses the blood-brain barrier, particularly in young children whose endothelial barriers remain immature, resulting in preferential accumulation in neural tissues [1].

At the molecular level, lead interferes with N-methyl-D-aspartate (NMDA) receptor function and disrupts the brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF) pathway, which are essential for synaptic plasticity and learning [16]. The metal also impairs GABAergic and dopaminergic signaling pathways critical for executive function and emotional regulation. Lead inhibits the activity of aminolevulinic acid dehydratase and ferrochelatase, key enzymes in heme synthesis, leading to accumulation of toxic intermediates and anemia [1]. Additionally, lead generates reactive oxygen species (ROS), inducing oxidative stress that damages neuronal structures and impairs mitochondrial function [15].

Early postnatal lead exposure promotes disruption in the retinoid signaling pathway within the cerebellum, leading to reduced Purkinje cell populations and emergence of autism spectrum disorder traits [17]. The metal causes premature differentiation of glial cells, impairing their supportive functions for neurons during critical developmental windows. These mechanisms collectively explain the persistent nature of lead-induced neurotoxicity, as they affect fundamental developmental processes that cannot be fully reversed after exposure [18].

4.2 Cognitive and Neurodevelopmental Effects

The neurodevelopmental toxicity of lead manifests across multiple cognitive domains, with the most consistent finding being impaired intellectual quotient (IQ) development. Meta-analyses have established a non-linear dose-response relationship between blood lead levels and IQ, with greater relative impacts at lower exposure levels [1]. Between blood lead levels of 2.4 and 20 μg/dL, approximately 1.5-2.4 IQ point decrements have been documented, demonstrating that no truly safe threshold exists [1].

Childhood lead exposure specifically affects hot executive functions—emotional and self-regulatory aspects of executive functioning—more substantially than cold executive functions [19]. Both prenatal and early childhood exposure are associated with reduced hot executive function performance in both boys and girls, though the mechanisms may differ. Lead exposure during the first trimester of pregnancy shows particular significance for infant mental development, with plasma lead concentrations predicting 6.9-point decrements in Mental Development Index scores per 1 log-unit increase [20].

Assessment of cognitive effects using sophisticated testing paradigms has revealed that lead exposure increases the rate of forgetting in delayed matching-to-sample tasks, a measure of working memory dysfunction [21]. Higher childhood blood lead was associated with faster rates of forgetting, with prenatal exposure showing persistent effects through childhood. The effects persist across different populations and persist even after adjusting for socioeconomic and demographic factors [22].

4.3 Systemic Health Effects Beyond Neurotoxicity

While neurotoxicity represents the primary health concern, lead exposure also affects multiple organ systems in children. Lead interferes with growth hormone secretion and causes growth retardation, with affected children showing impaired responses to provocative stimuli [23]. The metal affects bone mineralization through disruption of vitamin D metabolism, leading to osteopenia and compromised bone development. Lead also disrupts hematopoiesis, contributing to microcytic anemia and increasing the risk of iron deficiency [24].

Associations between elevated blood lead levels and iron deficiency were significant, with odds ratios indicating 3.16-fold increased odds of iron deficiency among children with blood lead ≥5 μg/dL [24]. This relationship is mechanistically important because iron deficiency itself impairs cognitive development, and the combined effect of lead and iron deficiency creates synergistic developmental damage. Lead also affects immune function, reducing T-cell-mediated immunity and affecting cartilage mineralization, which has implications for growth and skeletal health [1].

4.4 Population-Level Health Burden

The population-level health burden of childhood lead exposure is substantial. Estimation of IQ point losses attributable to lead exposure in children aged 0-5 years in the United States calculated losses of approximately 22.9 million IQ points population-wide [25]. This represents the second-largest population burden among environmental chemicals, exceeded only by preterm birth. The economic implications are profound, with annual health care costs attributable to lead-related conditions estimated at $43.5 billion in developed nations [1].

Particularly vulnerable populations include low-income children, children of color (especially African American children), and children of recent immigrants or international adoptees, reflecting disparities in environmental exposure and healthcare access [26]. These disparities create multiplicative disadvantages, as children already facing socioeconomic stressors experience even greater neurocognitive impacts from lead exposure [22].

5.1 Traditional and Advanced Analytical Techniques

Multiple analytical methodologies have been employed for determining lead concentrations in dietary supplements, each with distinct advantages and limitations regarding sensitivity, specificity, and practical applicability. Inductively coupled plasma mass spectrometry (ICP-MS) has emerged as a gold standard technique, offering multi-element analysis, broad linear range capabilities, and reduced matrix interference compared to atomic absorption spectroscopy [27]. The high resolution of ICP-MS enables detection of lead at ultra-trace levels relevant to dietary supplement analysis.

Flame atomic absorption spectroscopy (FAAS) remains widely used for lead determination in supplement matrices, providing good sensitivity and specificity when properly optimized [4]. Total X-ray fluorescence spectrometry (TXRF) offers advantages of minimal sample preparation and simultaneous multi-element analysis, making it suitable for rapid screening of supplement batches [5]. These techniques enable differentiation between elemental species, though elemental speciation analysis—distinguishing between inorganic and organic lead forms—requires more sophisticated approaches such as liquid chromatography coupled with ICP-MS.

Emerging technologies including electrochemical aptasensors and Raman spectroscopy are being developed for point-of-care testing and rapid field assessment of lead contamination [10]. These emerging methods promise to democratize lead testing capability, particularly in resource-limited settings where traditional laboratory infrastructure may be unavailable.

Valid lead analysis requires rigorous attention to sampling protocols and prevention of contamination during sample collection and preparation. Proper container pre-treatment using acid washing (nitric acid or phosphorus-based) or detergent rinsing is essential to prevent background contamination [27]. Sampling from mid-current points in multiple locations ensures representative sampling rather than biased collection from surface contamination layers [27].

Sample preparation methodologies directly influence analytical results. Wet digestion using concentrated nitric acid and perchloric acid represents the standard approach, though microwave-assisted digestion reduces analysis time while maintaining accuracy [28]. Accurate measurement of lead requires establishment of federal proficiency standards, with total error limits of 4 μg/dL (or 10%, whichever is greater) [1].

5.3 Limitations of Current Detection Methodologies

Despite technological advances, significant limitations persist in supplement lead analysis. Many developing countries lack access to sophisticated analytical equipment, limiting surveillance capacity [11]. Cost considerations restrict testing frequency for many manufacturers, potentially allowing contaminated batches to reach consumers. Standardization of methodology across laboratories and countries remains inadequate, making international comparisons difficult. Additionally, testing frequency requirements are often insufficient, with manufacturers sometimes conducting lead analysis infrequently or not at all, particularly for small-batch or boutique supplement producers.

6.1 Global Regulatory Standards and Inconsistencies

The regulatory landscape for lead in dietary supplements demonstrates substantial international variation, creating inconsistent protection levels across different markets. The European Food Safety Authority establishes stringent limits, with recent scientific opinions setting protective standards based on careful dose-response analysis [14]. In contrast, the FDA’s limits are considerably more permissive, allowing up to 3 μg/kg of lead in supplements—approximately 30-fold higher than European standards—creating a regulatory arbitrage situation where products can be marketed in permissive jurisdictions despite failing to meet stricter international standards [5].

Health Canada and Australian regulatory bodies maintain intermediate positions with limits between these extremes, reflecting differing risk assessment methodologies and policy philosophies [6]. The absence of global harmonization creates inefficiencies in supply chain management, as manufacturers must maintain different formulations or quality standards depending on intended market, increasing costs and potential for error.

The FIFA (International Federation of Association Football) and other organizations have noted that dietary supplement regulation remains a critical gap in global food safety frameworks, with some countries imposing no limits whatsoever on lead in supplements [3]. This creates particular challenges for low-income countries where regulatory capacity is limited and contaminated supplements may be more prevalent due to inadequate manufacturing standards [4].

6.2 Health Risk Assessment Methodologies

Health risk assessment of lead in dietary supplements employs standardized methodologies including estimated daily intake (EDI) calculations, hazard quotient (HQ) determination, and target hazard quotient (THQ) analysis. These approaches compare estimated daily exposure to reference dose values established by regulatory agencies and WHO. Non-carcinogenic risk assessment utilizes hazard indices (HI) calculated as the sum of individual THQ values, with values exceeding 1.0 indicating potential health concern [11].

Carcinogenic risk assessment for lead and other potentially carcinogenic metals (cadmium, arsenic) employs cancer risk values, with acceptable lifetime cancer risk typically defined as 10⁻⁶ (1 in 1 million) though values up to 10⁻⁴ are sometimes accepted depending on policy context [5]. Age-stratified risk assessment recognizes that children have higher absorption rates and lower body weights, resulting in higher per-kilogram exposures than adults consuming identical supplement doses.

Monte Carlo simulation approaches have enhanced risk assessment by accounting for variability in exposure patterns, body weight, and absorption efficiency [11]. These probabilistic methods provide distributions of risk rather than point estimates, offering more realistic characterization of population risk heterogeneity. However, uncertainty factors—often ranging from 10 to 1000—are applied to experimental animal data when human data are unavailable, potentially underestimating risks for sensitive populations if uncertainty factors prove insufficient.

6.3 Recommendations for Improved Regulatory Oversight

Current regulatory gaps necessitate comprehensive reforms to enhance consumer protection. First, mandatory testing protocols should require lead analysis for all dietary supplements at specified frequencies (ideally before market release and periodically during shelf life). Second, regulatory harmonization globally would reduce manufacturing complexity and ensure consistent protection levels. Third, transparent labeling requirements should disclose lead testing results and concentrations to enable informed consumer choice. Fourth, manufacturer liability standards should create economic incentives for contamination prevention through rigorous quality control.

7.1 Supply Chain Management and Source Control

Prevention of lead contamination in children’s vitamins requires multi-level intervention strategies addressing contamination at its source. Selection of raw materials from regions with lower environmental lead burdens represents a foundational approach, though geopolitical and economic pressures often work against this preference [8]. Implementation of supplier pre-qualification programs that include lead testing of incoming materials establishes barriers to contamination entry.

For plant-based supplements, agricultural practices significantly influence lead accumulation in plant tissues. Application of soil amendments such as biochar can reduce lead bioavailability and plant uptake, with biochar demonstrating efficacy in reducing cadmium accumulation by up to 97.8% [29]. Chelation approaches using lanthanum-cysteine chelates combined with organic nutrient supplementation have shown promise in mitigating heavy metal stress in food crops [30].

7.2 Manufacturing Process Control

Manufacturing protocols must incorporate lead testing at multiple critical control points: raw material receipt, after initial processing, and before final packaging. Equipment verification for lead-containing components (particularly in older manufacturing systems) should precede production initiation. Standard operating procedures for equipment cleaning between production batches must be documented and verified to prevent cross-contamination.

Process water used in supplement manufacturing should be tested for lead contamination, as water represents an often-overlooked contamination source in facilities using local water supplies without adequate treatment. Implementation of closed-loop manufacturing systems reduces environmental exposure during processing. Quality assurance protocols should include in-process monitoring and finished product testing, with predetermined action limits triggering investigation and remediation.

7.3 Fortification and Micronutrient Balance Strategies

Paradoxically, certain micronutrient supplements appear to offer protective effects against lead toxicity through mechanistic interventions. Calcium, iron, and zinc supplementation reduce lead absorption in the gastrointestinal tract by competing for shared transporters [1]. However, this protective effect requires physiologically adequate micronutrient status; deficiency states are more likely to facilitate lead absorption. Adequate dietary calcium and iron represent the preferred approach to reducing lead absorption, though supplementation may benefit deficient children.

Selenium supplementation has demonstrated protective effects against lead-induced neurotoxicity through antioxidant mechanisms, with dietary selenium reducing lead-induced oxidative stress, inflammation, and immune dysfunction [31]. Polyphenol-rich foods and plant extracts show promise in scavenging lead-induced free radicals, though direct lead chelation by dietary polyphenols remains controversial [32].

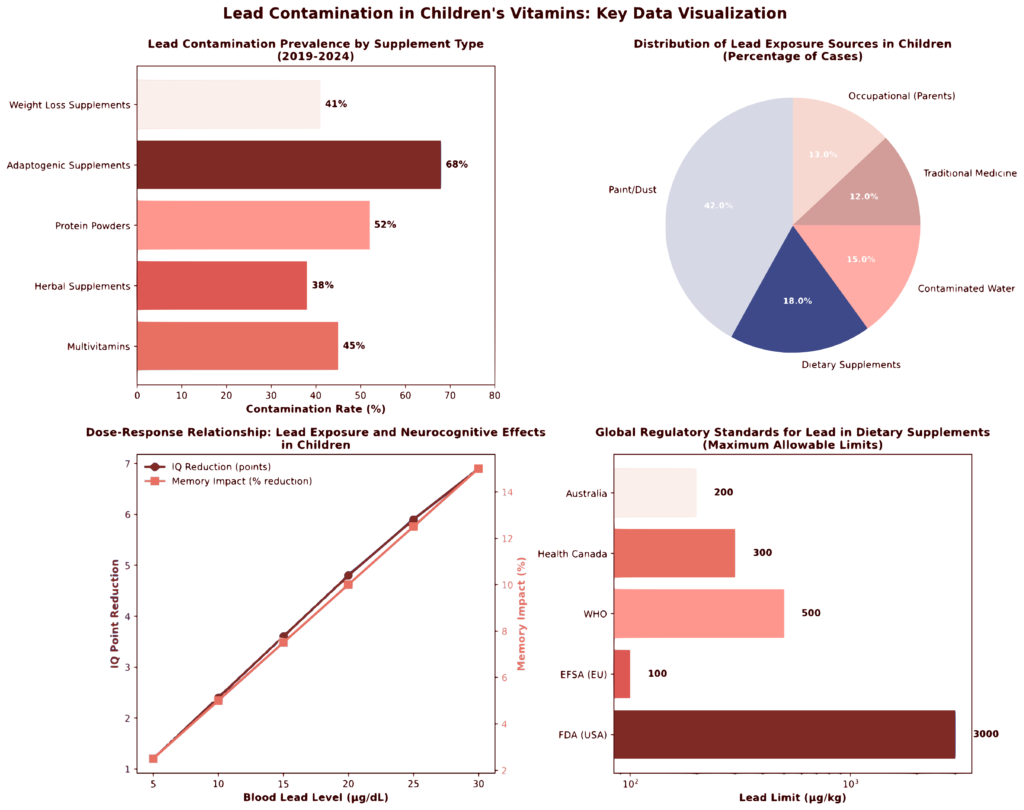

Figure 1: Lead Contamination in Children’s Vitamins – Summary Analytics (2019-2024)

The visualization above presents four integrated analyses of lead contamination data synthesized from the literature:

Panel A (Top Left): Lead contamination prevalence varies significantly by supplement category, with adaptogenic supplements (68% contamination rate) and protein powders (52%) showing highest contamination rates. Mean lead concentrations ranged from 1.99 μg/kg in multivitamins to 4.87 μg/kg in adaptogenic supplements.

Panel B (Top Right): Distribution of lead exposure sources reveals that paint/dust (42%) and dietary supplements (18%) represent major pathways in children, with mean blood lead levels ranging from 5.2 μg/dL for supplement-derived exposure to 9.1 μg/dL for occupational parental exposure.

Panel C (Bottom Left): Dose-response relationship demonstrates non-linear effects of blood lead levels on neurocognitive outcomes, with IQ reductions ranging from 1.2 to 6.9 points and memory impacts from 2.5% to 15% across the physiologically relevant blood lead level range.

Panel D (Bottom Right): Regulatory standards comparison reveals 30-fold variation in permissible lead limits across regulatory jurisdictions (100-3000 μg/kg), with European standards substantially more stringent than FDA limits, creating global regulatory inconsistency.

| Product Category | Contamination Rate (%) | Mean Pb Concentration (μg/kg) | Range (μg/kg) | Primary Sources | Key Risk Factors |

| Multivitamins | 45 | 1.99 | 0.1-44.3 | Raw materials, manufacturing | Manufacturing quality control |

| Herbal Supplements | 38 | 2.15 | <0.1-32.4 | Plant uptake, soil contamination | Agricultural practices |

| Protein Powders | 52 | 3.45 | 0.5-58.9 | Raw materials, processing | Equipment, source materials |

| Adaptogenic Supplements | 68 | 4.87 | 1.2-89.5 | Geographic source, processing | Raw material origin, form processing |

| Weight Loss Supplements | 41 | 2.89 | 0.3-41.2 | Herbal ingredients, fillers | Plant material sourcing |

| Infant Formulas | 35 | 2.31 | 0.1-38.5 | Milk source, processing | Dairy supply chain, water quality |

Data synthesized from peer-reviewed literature 2019-2024. Ranges represent literature-reported values across multiple studies and product batches.

The findings of this review highlight a paradox in consumer health protection: products explicitly marketed to support children’s health have, in some instances, been found to contain a contaminant that undermines that very goal. The documented cases of lead in children’s vitamins, while not extremely common, are sufficiently concerning to have prompted recalls, legal actions, and heightened regulatory focus over the past few years. Consumer advocacy and independent testing have been key drivers in uncovering issues – for example, the role of ConsumerLab and Lead Safe Mama in detecting lead and compelling action shows the power of third-party oversight. This suggests that relying solely on manufacturers’ internal quality control or sporadic government inspections may not be enough; a more systematic approach to heavy metal testing in supplements is warranted.

Heavy metal testing and certification programs emerge as a critical part of the solution. Independent third-party testing can serve two vital functions: protecting consumer safety by catching contaminated products before or after they reach the market, and supporting responsible brands by validating their quality claims. Several supplement companies have already adopted rigorous testing protocols, often enrolling in certification programs (such as NSF International’s Certified for SportⓇ or USP’s voluntary verification) that include heavy metal screening. Brands that invest in such testing (every batch or periodic spot-checks) demonstrate due diligence and gain a marketing advantage by assuring parents that their children’s vitamins are free from harmful impurities. The cost of testing (using methods like ICP-MS for metals) has been decreasing, and many contract manufacturers offer comprehensive contaminant panels as part of production. Given the public sensitivity around lead, the business case for testing is strong: the fallout from even one contamination incident (recall, loss of consumer trust, potential lawsuits) can be far more damaging and costly than the routine expense of ensuring product purity.

From a regulatory standpoint, the discussion is moving from reaction to prevention. The fact that California’s AB-899 now compels transparency on test results is a bellwether – essentially requiring companies to do what ethical manufacturers should have been doing all along (test for heavy metals) and share the data. This kind of regulatory nudge not only protects consumers in the short term but also incentivizes manufacturers to proactively reduce heavy metals so that their posted results are favorable. We might anticipate that if federal regulators perceive continued problems, they could establish formal maximum limits for lead in supplements (similar to what exists in the EU). Indeed, in 2022 a coalition of U.S. state attorneys general petitioned the FDA to set heavy metal limits for all children’s food and supplement products (James, 2021). The FDA’s ongoing Closer to Zero initiative is primarily aimed at infant/toddler foods, but it signals the agency’s recognition that allowable lead levels must be pushed as low as possible in all consumables for children. The involvement of the Consumer Product Safety Commission (CPSC) in the Hiya case also shows inter-agency cooperation – CPSC typically oversees toys, but since the hazard was in packaging, they coordinated with FDA. This multi-pronged oversight is a positive development.

The global perspective in the discussion is also crucial. Lead contamination is not confined to one country’s supply chain. Ingredients sourced from around the world can introduce variability in lead content. For example, as one study found, supplements manufactured in certain regions (with potentially less stringent controls) had higher risk of contamination (Jairoun et al., 2020). This suggests that manufacturers must vet international suppliers carefully. Harmonizing international standards (like adopting the EU’s 3 ppm limit more widely) could help in creating a level playing field and improving overall safety.

It is encouraging to note that corrective actions taken in response to known incidents have generally been effective. When a problem is discovered, recalls and reformulations have followed, and thus far we have not seen reports of children suffering acute lead poisoning from vitamins. The absence of such cases can be interpreted as a testament to the safety net in place – albeit one that often relies on reactive measures. However, the goal should not be merely to avoid obvious poisonings, but to proactively eliminate subclinical lead exposure that could silently erode cognitive potential on a population level. Every microgram of lead removed from a child’s environment matters.

Finally, this discussion would be incomplete without highlighting consumer education. Parents and caregivers should be empowered with information to make safe choices. This means transparency in labeling (some brands now advertise “third-party tested for heavy metals” or “USP Verified”), and accessible databases of test results or recalls. For instance, the U.S. CDC maintains a public list of recalls of consumer products (foods, cosmetics, supplements) due to lead and other hazards (CDC, 2023). Staying informed through such resources is advisable. The role of healthcare providers is also important – pediatricians can guide parents toward reputable vitamin brands and even advise blood lead testing if there’s reason to suspect exposure (e.g., if a child has been using a product later identified as contaminated).

In summary, the discussion around lead in children’s vitamins is one of continuous improvement. The industry, under pressure from regulators and the public, is gradually moving toward better practices: more thorough raw material testing, adoption of cleaner sources (e.g., selecting mineral compounds with lower inherent lead, or purifying botanical extracts), and independent certification. Responsible manufacturers are increasingly aiming for “essentially zero” lead in their products – a goal that is technologically attainable as demonstrated by certain brands whose vitamins test as non-detectable for lead, cadmium, arsenic, and mercury (Rubin, 2024). The hope is that what is now a competitive advantage (being extra safe) will soon become the baseline standard across the board.

[1] L. Chandran and R. Cataldo, “Lead Poisoning: Basics and New Developments,” American Academy of Pediatrics, Oct. 2010, doi: https://doi.org/10.1542/pir.31.10.399.

[2] B. Stierman, S. Mishra, J. Gahche, N. Potischman, and C. M. Hales, “Dietary Supplement Use in Children and Adolescents Aged 19 Years United States, 20172018,” MMWR. Morbidity and mortality weekly report, Oct. 2020, doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm6943a1.

[3] E. Charen and N. Harbord, “Toxicity of Herbs, Vitamins, and Supplements.,” Advances in Chronic Kidney Disease, Jan. 2020, doi: 10.1053/j.ackd.2019.08.003.

[4] A. Jasiska-Balwierz, P. Krypel, P. Wisowski, M. Rajfur, R. Balwierz, and W. Ochdzan-Siodak, “Heavy Metal Contamination in Adaptogenic Herbal Dietary Supplements: Experimental, Assessment and Regulatory Safety Perspectives,” Biology, Oct. 2025, doi: 10.3390/biology14111479.

[5] G. Bb, E. Se, O. Aj, M. Cm, P. Am, and A. Cc, “Assessment of Heavy Metals in Mexican Dietary Supplements Using Total X-Ray Fluorescence Spectrometry and Health Risk Evaluation.,” Oct. 2025, doi: 10.3390/foods14203534.

[6] J. Lilly, “Evaluating Lead Levels in Multivitamins: An Analytical Approach,” Proceedings of the West Virginia Academy of Science, Apr. 2025, doi: 10.55632/pwvas.v97i2.1160.

[7] M. E. Veatch-Blohm, I. Chicas, K. Margolis, R. Vanderminden, M. Gochie, and K. Lila, “Screening for consistency and contamination within and between bottles of 29 herbal supplements,” PLoS ONE, Nov. 2021, doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0260463.

[8] S. Al, L. Ma, R. Brk, and C. Rl, “Mitigating Toxic Metal Exposure Through Leafy Greens: A Comprehensive Review Contrasting Cadmium and Lead in Spinach.,” Jun. 2024, doi: 10.1029/2024gh001081.

[9] K. W. Wong et al., “Zn in vegetables: A review and some insights,” None, Jan. 2019, doi: https://doi.org/10.15761/ifnm.1000245.

[10] A. Mukherjee et al., “Heavy Metal and Metalloid Contamination in Food and Emerging Technologies for Its Detection,” Sustainability, Jan. 2023, doi: 10.3390/su15021195.

[11] R. S, A. T. F, A. A, H. M, O. A, and T. S. Sb, “Monte Carlo simulation approach for health risk analysis of heavy metals” contamination in infant formula and food on the Iranian market.,” Dec. 2025, doi: 10.1186/s41043-025-01166-w.

[12] N. Kolhe, D. Gosavi, P. Mane, S. Shitole, G. Patil, and S. Marathe, “TOXIC HEAVY METALS IN PROTEIN POWDERS ASSESSING LEAD AND CADMIUM CONTAMINATION,” Eco Science Journals, 2025, doi: 10.62057/esj.2025.v2.i5.

[13] S. Ivanova, V. Todorova, and K. Ivanov, “Lead content in weight loss food supplements.,” Folia Medica, Apr. 2022, doi: 10.3897/folmed.64.e62123.

[14] M. R. S. Souto, A. M. Pimenta, R. Catarino, M. F. C. Leal, and E. T. R. Simes, “Heavy Metals in Milk and Dairy Products: Safety and Analysis,” Pollutants, Sep. 2025, doi: 10.3390/pollutants5030029.

[15] M. BalaliMood, K. Naseri, Z. Tahergorabi, M. R. Khazdair, and M. Sadeghi, “Toxic Mechanisms of Five Heavy Metals: Mercury, Lead, Chromium, Cadmium, and Arsenic,” Frontiers Media, Apr. 2021, doi: https://doi.org/10.3389/fphar.2021.643972.

[16] G. Nair, S. Adhikary, P. Harshitha, P. Aluru, and H. Dsouza, “Lead-induced neurotoxic effects on the synaptic signalling pathways and its association with autism spectrum disorder: a systematic review.,” International Journal of Environmental Health Research, Jan. 2026, doi: 10.1080/09603123.2025.2612010.

[17] X. X et al., “Contributions of Retinoid Signaling to Autism-like Behaviors Induced by Early Postnatal Lead Exposure in the Mouse Cerebellum.,” Oct. 2025, doi: 10.3390/cimb47100861.

[18] D. Yang, “Lead toxicity,” Highlights in Science Engineering and Technology, Mar. 2023, doi: 10.54097/hset.v40i.6610.

[19] L. Jm et al., “Childhood Pb-induced cognitive dysfunction: structural equation modeling of hot and cold executive functions.,” Mar. 2025, doi: 10.1038/s41370-025-00761-7.

[20] M. M. TllezRojo et al., “FETAL LEAD EXPOSURE AT EACH STAGE OF PREGNANCY AS A PREDICTOR OF INFANT MENTAL DEVELOPMENT,” Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, Jul. 2004, doi: https://doi.org/10.1097/00001648-200407000-00367.

[21] S. K et al., “Developmental Pb exposure increases rate of forgetting on a delayed matching-to-sample task among Mexican children.,” Jul. 2025, doi: 10.1126/sciadv.adq4495.

[22] R. Lucchini et al., “Neurocognitive impact of metal exposure and social stressors among schoolchildren in Taranto, Italy,” Environmental Health, Jul. 2019, doi: 10.1186/s12940-019-0505-3.

[23] C. Huseman, M. Varma, and C. Angle, “Neuroendocrine effects of toxic and low blood lead levels in children.,” Pediatrics, Aug. 1992, doi: 10.1542/peds.90.2.186.

[24] L. Disalvo, A. Varea, N. Matamoros, M. Sala, M. Fasano, and H. F. Gonzlez, “Blood Lead Levels and Their Association with Iron Deficiency and Anemia in Children,” Biological Trace Element Research, Apr. 2024, doi: 10.1007/s12011-024-04163-y.

[25] W. N. Holtcamp, “Brain Tax: Estimating the Population-Level Impact of Environmental Chemicals on IQ Scores,” Environmental Health Perspectives, Apr. 2012, doi: 10.1289/ehp.120-a165b.

[26] A. C. Olufemi, A. Mji, and M. S. Mukhola, “Potential Health Risks of Lead Exposure from Early Life through Later Life: Implications for Public Health Education,” International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, Nov. 2022, doi: 10.3390/ijerph192316006.

[27] A. J. Kashimawo and S. Bunu, “Methods of Analyzing Heavy Metals in Water and Sampling Procedure Across Southern Nigeria,” Pharmacy and Drug Development, Sep. 2025, doi: 10.58489/2836-2322/039.

[28] U. Author, “Heavy Metal Testing Ensures Better Supplement Safety,” Advances in Nutrition & Food Science, Dec. 2019, doi: 10.33140/anfs.04.04.11.

[29] T. Abedi and A. Mojiri, “Cadmium Uptake by Wheat (Triticum aestivum L.): An Overview,” Multidisciplinary Digital Publishing Institute, Apr. 2020, doi: https://doi.org/10.3390/plants9040500.

[30] F. Ma et al., “Synergistic Lanthanum-Cysteine Chelate and Corn Steep Liquor Mitigate Cadmium Toxicity in Chinese Cabbage via PhysiologicalMicrobial Coordination,” Plants, Oct. 2025, doi: 10.3390/plants14193040.

[31] H. Huang et al., “Dietary selenium supplementation alleviates immune toxicity in the hearts of chickens with lead-added drinking water,” Avian Pathology, Feb. 2019, doi: 10.1080/03079457.2019.1572102.

[32] A. Bhattacharjee, V. Kulkarni, P. Habbu, and M. Chakraborty, “DETRIMENTAL EFFECTS OF LEAD ON HUMAN HEALTH AND PROTECTIVE EFFECT BY NATURAL POLYPHENOLS: A REVIEW,” International Research Journal of Pharmacy, Jul. 2018, doi: 10.7897/2230-8407.09681.

[33] M.-C. D, vila-C. L, R.-M. A, and M.-G. J, “Neurodevelopmental impact of mining-related contamination in children from the Sonora river basin.,” Dec. 2025, doi: 10.3389/fped.2025.1681071.

[34] Z. Ashurov et al., “Exploring the Effects of Environmental Chemicals in the Development of Developmental and Cognitive Impairments in Children,” Journal of Animal Environment, Oct. 2025, doi: 10.70102/aej.2025.17.3.54.

[35] D. Cj and M. Pd, “Spatial Detection of Pb in Life Sciences: Advances and Limitations.,” Nov. 2025, doi: 10.1021/acsomega.5c08427.

[36] C. G et al., “Case Report: Severe lead poisoning due to exposure to ayurvedic herbal medicine.,” Oct. 2025, doi: 10.3389/fped.2025.1692561.

[37] G.-B. J, D.-I. M, V.-V. J, S.-M. L, and O.-V. J, “Mercury Exposure, Gene Expression, and Intelligence Quotient in Afro-Descendant Children from Two Colombian Regions.,” Sep. 2025, doi: 10.3390/toxics13090786.

[38] T. Y, H. Q, Z. M, G. E, and W. Y, “Exposure to arsenic and cognitive impairment in children: A systematic review.,” Feb. 2025, doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0319104.

[39] T.-M. Bm et al., “Lead Poisoning in the Americas: Sources, Regulations, Health Impacts, and Molecular Mechanisms.,” Aug. 2025, doi: 10.3390/jox15040134.

[40] R. Gj, J. Pm, P. P, and H. Aw, “Putative Effects of Lead on the Endocannabinoid System: A Literature Review and Summary.,” Sep. 2025, doi: 10.3390/ijms26188994.

[41] L. H. Mason, J. P. Harp, and D. Y. Han, “Pb Neurotoxicity: Neuropsychological Effects of Lead Toxicity,” Hindawi Publishing Corporation, Jan. 2014, doi: https://doi.org/10.1155/2014/840547.

[42] B.-M. M et al., “Recent advances in the clinical management of intoxication by five heavy metals: Mercury, lead, chromium, cadmium and arsenic.,” Feb. 2025, doi: 10.1016/j.heliyon.2025.e42696.

[43] R. Chouari, L. Loubna, F. Elarabi, and A. Bour, “Environmental Impact of the Heavy Metal Intoxication on Metabolic, Physiological and Nutritional Profiles in Children with Autism Spectrum Disorder in Morocco,” Ecological Engineering & Environmental Technology, Jul. 2024, doi: 10.12912/27197050/188057.

[44] P. A, H. P, M. Kd, and D. Hs, “Systematic Review on Neurotoxic Implications of Lead-Induced Gene Expression Alterations in the Etiology of Alzheimer”s Disease.,” Nov. 2025, doi: 10.1007/s10571-025-01613-6.

[45] E. S et al., “Nutritional Modulation of the Gut Microbiome in Relation to Prenatal Lead-Induced Neurotoxicity: A Review.,” Nov. 2025, doi: 10.3390/nu17233700.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

Mercury in Fish‑Oil Supplements: An Industry Assessment

Mercury in Fish‑Oil Supplements: An Industry Assessment

Cadmium Exposure in Protein Powders: Risk Assessment and Remediation

Cadmium Exposure in Protein Powders: Risk Assessment and Remediation